The world’s largest tech companies are on track to devote as much as $400B this year to data centers and chips as they race to build out artificial intelligence.

The spending spree is single-handedly bolstering U.S. economic growth, but in recent months, the rumblings of a looming AI bubble that began last year have grown louder.

A growing chorus of investors, economists and industry observers is raising red flags about the escalating price tag of data center investment and the feverish stock market growth it has spurred, even as reports show AI hasn’t created corporate profits. They say the hype will inevitably collide with economic reality and create the “mother of all financial bubbles.”

Bisnow/created with assistance from ChatGPT

But the data center real estate world isn’t as worried. Several industry leaders tell Bisnow that while they have seen new risks arising this year, including a greater reliance on debt and the proliferation of AI computing startups, they believe the foundations of the data center building boom remain solid.

“There’s a good balance of supply and demand, so I personally do not think we’re in a bubble,” said Carl Beardsley, JLL’s head of data center capital markets.

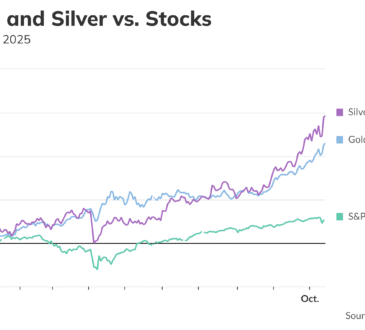

Compared to the waves of capital investment that followed other transformative technologies, from the automobile to the internet, the AI infrastructure build-out is unique in how quickly the industry has become the lynchpin of the U.S. economy. Economists say GDP growth in the first half of 2025 was almost entirely driven by investment in data centers and computing gear, and more than 75% of stock market appreciation since the end of 2022 has come from AI-focused companies.

Developers, analysts and economists acknowledge the possibility of an AI stock market correction that could cause tech firms to reduce spending. But even if demand for AI computing slows, they said they see no signs that the data center building boom has created a real estate bubble that might burst.

While a dramatic slowdown in demand would have significant economic implications, they said it wouldn’t trigger a chain reaction of economic destruction with a blast radius anything like the financial crises following the collapse of the dot-com bubble in 2000 or the housing bubble in 2008.

“The wheat and the chaff might be separated in an environment where capital flows are less robust, but right now I don’t think we see a bubble yet,” Moca Systems principal economist Brandon Michalski said.

Wall Street’s AI Anxiety

Much of the public speculation about an AI bubble has been focused on whether the stock market has dramatically overvalued the technology’s potential and is poised to plunge back to earth.

The “magnificent seven” tech companies — Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla — together account for close to one-third of the S&P 500’s total value and have all bet their futures on AI, an unprecedented concentration of risk around a single technology.

Michalski said there is growing unease around Wall Street’s “frothy” valuations of these behemoths, which are increasingly pegged to projections of AI-driven revenue growth.

Tech giants have pushed beyond traditionally accepted limits with their infrastructure spending — ramping up capital expenditures to as much as 50% of income — because Wall Street has largely bought in to the grandiose projections their executives make for AI’s potential. Figures like Meta Platforms’ Mark Zuckerberg frame AI as the bedrock of a societal shift surpassing the industrial revolution that is poised to dismantle all barriers to human progress.

But selling AI in such messianic terms can cause a crisis of faith if the promised machine god fails to materialize. And there are signs that Wall Street is getting impatient as AI revenues remain well short of the massive infrastructure costs.

Skeptics say there is new evidence that AI’s economic potential is more modest than tech leaders envision and that firms are running out of time to make AI profitable. In August, markets plummeted following a Massachusetts Institute of Technology report showing that 95% of corporate generative AI pilots were failing.

A market correction triggered by a shift in Wall Street’s AI sentiment — beyond its impact on the global economy — would likely dramatically decrease capital spending on data centers, graphics processing units and other AI infrastructure.

“An imminent bubble would really impact those capital flows,” Michalski said.

Even the most bullish AI proponents, from Zuckerberg to OpenAI’s Sam Altman, say it is likely the infrastructure build-out will lead to a stock market bubble bursting that will slow AI capex.

This kind of rushed capital spending is never entirely rational and efficient, they say, as companies inevitably overspend on technology, equipment and infrastructure before realizing too late they need to pull back.

“There’s definitely a possibility … based on past large infrastructure build-outs and how they led to bubbles, that something like that could happen here,” Zuckerberg told the Access podcast last month.

‘Wildly Different’ Than The Dot-Com Bubble

A dramatic spending pullback may be inevitable, but there is consensus across the digital infrastructure space that, if the capex tap were shut off today, the sector is in a far less perilous position than on the eve of the dot-com bust that devastated the industry a quarter-century ago.

Applied Digital CEO Wes Cummins chafes at comparisons between this moment and the dot-com collapse. Beyond bad investments in spurious online business models, that boom was a speculative infrastructure bubble. Companies spent billions building out fiber and data centers for customers they anticipated would emerge quickly. That demand didn’t materialize for years, resulting in a flood of defaults.

But this AI infrastructure build-out has seen almost no speculative development. Far from a risk of overbuilding, data center inventory continues to trail behind demand. Few large-scale data center projects are financed and built without a credit-grade lease in place. Even if demand for AI computing slows, the amount of vacant inventory would be minimal, Cummins said.

“We’re in a very different situation here, where the applications are way out in front in the data center and fiber infrastructure, where we’re really just trying to play catch-up,” Cummins said. “The demand continues to outstrip supply, which is wildly different than what we saw in the tech bubble.”

The data center sector has been saved from becoming an oversupplied bubble in part by the shortages of power and critical equipment that have constrained development, Michalski said. Construction labor shortages and yearslong wait times for equipment from generators to switchgear have plagued the industry for the past five years, and solving these problems has been a central focus for the sector.

But Michalski said these shortages haven’t been entirely unintentional. He said builders and equipment vendors are used to boom-and-bust cycles and are hesitant to expand their workforce or make large capital investments to increase production that might come back to bite them when the market declines.

Because of this cautious approach, the economic fallout down the development value chain in the wake of a Big Tech capex pullback wouldn’t be as devastating as many expect, he said.

“Construction firms have not gone all-in. They’ve been burned before, and the ones that get burned don’t exist in the next cycle, so they’re hesitant to jump in at every opportunity,” Michalski said. “The manufacturers of the equipment, the switchgear and turbine manufacturers, they haven’t gone all-in yet either and meaningfully scaled up production.”

Another key difference is the stability of the firms involved. Whereas the companies fueling the dot-com bubble were startups with few real revenues, weak balance sheets and unsustainable business models, the AI investment wave is being mainly fueled by the world’s largest, best-capitalized companies. Even if computing needs decrease, these firms would honor existing leases.

ValorC3 Data Centers CEO Jim Buie said the sector’s stability extends to lenders. Data center lending is dominated by large investment firms’ infrastructure arms, which have extensive experience and realistic expectations for market turbulence.

“The majority of investment going into this space are infrastructure funds, which is very different from earlier financial bubbles where you had a lot of vendor financing, you had a lot of bad financial backing,” Buie said.

Not A Bubble, But Getting Bubblier

Still, there have been changes across the data center sector this year that have introduced more risk into the AI infrastructure ecosystem. A demand downturn would see the emergence of winners and losers, and experts say the number of potential losers may be growing.

For most of the AI boom, the tech giants leading the charge had funded capex with cash flow. But over the past eight months, the building boom has suddenly become much more reliant on debt, with companies like Oracle planning on borrowing $100B over the next four years to fund data center development for OpenAI.

To skeptics, this growing use of debt shows that the players at the center of the AI infrastructure boom are overspending. Oracle’s debt-to-equity ratio is more than 400% higher than other hyperscalers, and Moody’s has assigned a negative outlook to its credit.

The increasing use of asset-backed securities by hyperscalers, third-party developers and AI-focused cloud providers to fund development has also raised concerns. As riskier players and debt structures become more prominent, analysts like TS Lombard’s Dario Perkins see parallels to the dot-com bubble’s final days.

“I wouldn’t touch this stuff now,” Perkins told Axios. “We’re much closer to 2000 than 1995.”

There is also wariness around the prevalence of circular investment in the AI data center ecosystem, particularly Nvidia’s massive investments in OpenAI and other major customers to help build data centers. To some observers, Nvidia is effectively funding the purchase of its own products, inflating the market with the kind of “vendor financing” that helped trigger the dot-com crash.

Data center industry leaders largely dispute this characterization. While dot-com-era vendor financing came as debt that caused a chain reaction when revenue never materialized, Nvidia is taking an equity stake in its customers, which Applied Digital’s Cummins said “doesn’t leave this ticking time bomb of high-interest debt.”

But perhaps the most significant risk factor spreading through the data center landscape over the past year has been the rise of “neoclouds,” AI-focused cloud providers like CoreWeave that offer on-demand access to the GPU computing critical for AI. The sector has a compound annual growth rate in revenue of 82% since 2021, according to JLL.

While CoreWeave is by far the largest player in the space, nearly 200 smaller neocloud operators exist. Skepticism surrounds these new providers’ longevity, and the increasing inventory leased to AI startups, rather than credit-grade tenants, invites comparisons to the dot-com bubble.

For now, neoclouds are being treated with caution. Data center providers typically require neocloud leases to be heavily collateralized, or “backstopped,” by one of the major credit-grade tech firms. Google and Microsoft have backstopped leases from neoclouds Fluidstack and Nebius Group, respectively, guarantees that allowed the issuance of mortgage-backed securities tied to those data centers.

As the risk attached to these upstart companies becomes linked to the industry’s hyperscale stalwarts and integrated into the debt market, the blast radius of potential capex pullback is getting larger. Even AI bulls like Applied Digital’s Cummins acknowledge that a wider share of demand is coming from firms that wouldn’t require an “insane calamity” for their business to evaporate.

“I don’t want to FOMO our company into a bad position in the future, so we’re still really focused on those investment-grade customers,” Cummins said. “It’s a lot of excitement right now, but what does it look like six or 12 months from now?”