Rare earths are minerals used to make magnets, crucial to many sectors from the automotive, electronics and defense industries to renewable energy.

Unlike their name, they appear to be available in several countries worldwide, but new export controls of the leader in the field, China, have reignited the concerns over the global supply of the elements, making them a new area of dispute amid shifting geopolitical tides.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent slammed export curbs imposed by Beijing earlier this month on technologies used for rare-earth mining, smelting and other processing steps.

Bessent said on Thursday it was “China versus the world.”

Here are some key things to know:

Are they really rare?

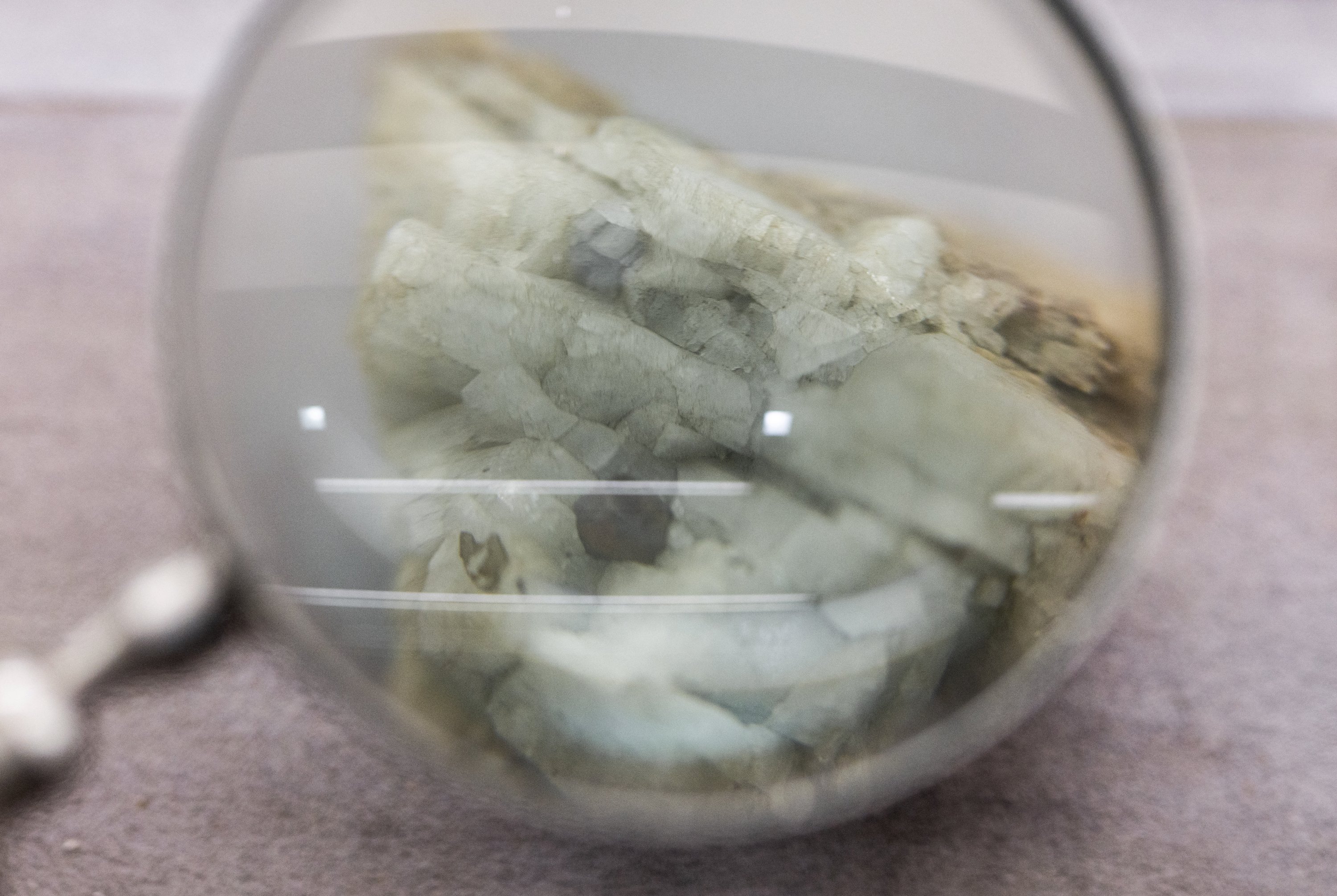

Not really. With names like dysprosium, neodymium and cerium, rare earths are a group of 17 heavy metals that are abundant throughout the Earth’s crust.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated in 2024 that there were 110 million tons of deposits worldwide.

That includes 44 million in China – by far the world’s largest producer.

A further 22 million tons are estimated in Vietnam and 21 million in Brazil, while Russia has 10 million and India nearly 7 million tonnes.

But mining the metals requires heavy chemical use that results in toxic waste and has caused several environmental disasters.

Many countries are also wary of shouldering the high financial costs for production.

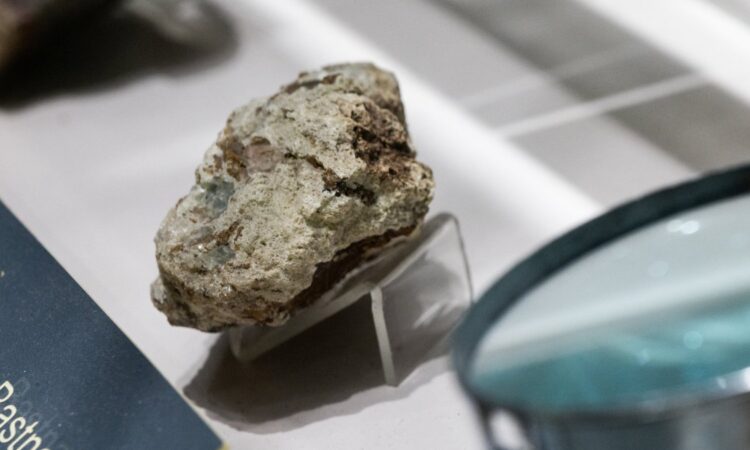

The minerals are often found in minute ore concentrations, meaning large amounts of rock must be processed to produce the refined product, often in powder form.

Why are they special?

The 17 rare earths are found in a wide variety of everyday and high-tech devices, from light bulbs to guided missiles.

Europium is crucial for television screens, cerium is used for polishing glass and refining oil, lanthanum makes a car’s catalytic converters operate – the list of uses in today’s economy is virtually endless.

All have unique properties that are largely irreplaceable or can be substituted only at prohibitive costs.

Neodymium and dysprosium, for example, allow the fabrication of almost permanent, super-strong magnets that require little maintenance – making viable the placement of ocean wind turbines to generate electricity far from the coastline.

China in the lead

For decades, China has made the most of its reserves by investing massively in refining operations, often without the strict environmental oversight required elsewhere.

Beijing has also filed a huge number of patents on rare earth production, an obstacle to companies in other countries hoping to launch large-scale processing.

As a result, many firms find it cheaper to ship their ore to China for refining, reinforcing the world’s reliance.

Beijing began in April requiring domestic exporters to apply for a licence, seen as a response to U.S. tariffs that sparked alarm in Washington over slower supplies of rare earths.

In June, U.S. President Donald Trump hailed a deal that would see China provide the vital elements “up front.”

But supply chains had not fully stabilized, with bureaucratic delays and selective approval still preventing many firms from ensuring timely access to the materials, even before China expanded its restrictions.

Strategy and supply

The U.S. and the European Union get most of their supply from China.

Both are trying to boost their own production and better recycle what they use to reduce dependence on Beijing.

At the height of a U.S.-China trade dispute in 2019, Chinese state media suggested that rare earth exports to the U.S. could be cut in retaliation for American measures, sparking fear among manufacturers.

Back in 2010, Japan saw the pain of being cut off when China halted rare earth exports over a territorial conflict.

Since then, Tokyo has pushed hard to diversify supplies, signing deals with the Australian group Lynas for production from Malaysia and ramping up its recycling capabilities.