DNR: Vehicle collisions have killed 60 moose in UP in four years | News, Sports, Jobs

- A bull moose photographed on a trail camera in the core Michigan moose range in the western Upper Peninsula. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

- A moose crossing sign along U.S. 41 in Greenwood in Marquette County, one of the moose-vehicle crash hotspots in the Upper Peninsula. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

- A dead bull moose is shown in the grass along an Upper Peninsula highway after a moose-vehicle crash. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

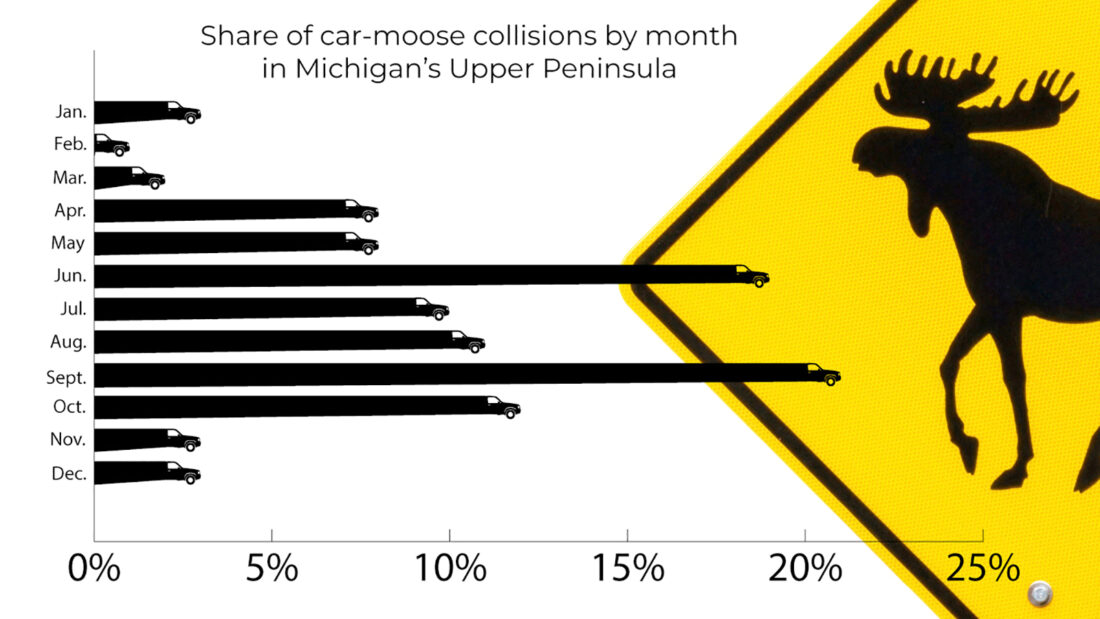

- A graph shows months and the percentage of occurrence of moose-vehicle crashes in the Upper Peninsula. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

A bull moose photographed on a trail camera in the core Michigan moose range in the western Upper Peninsula. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

Sixty moose have been killed in vehicle collisions over the past four years in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, with most of the crashes occurring on stretches of highway in the western U.P.

The fall and summer months, when moose are particularly active, are the most common times for collisions. About a third of all moose deaths from vehicle collisions occur in September and October, according to statistics compiled by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and the Michigan Department of Transportation.

On June 17, a female moose raising twin calves was killed by a vehicle at one of the hotspots – U.S. 141 in northern Iron County – likely removing three moose from the population because calves are dependent on their mother.

Over the past decade, the moose population in Michigan’s core range — Baraga, Marquette and Iron counties — has remained between 300 and 500 animals, and DNR wildlife biologists are researching the reasons behind why the population has remained relatively stagnant.

There have been no known human deaths from moose-vehicle collisions, but the potential is always there when a car traveling 55-65 mph or more meets a 1,000-pound animal, said Tyler Petroelje, the DNR’s northern Michigan wildlife research specialist.

A moose crossing sign along U.S. 41 in Greenwood in Marquette County, one of the moose-vehicle crash hotspots in the Upper Peninsula. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

“In a sense, Michigan has been very lucky,” Petroelje said. “But at the same time, I think that’s one of those things that is a reality – it could happen at any point.”

Moose-vehicle collision hotspots

Since 1984, at least 266 moose have been hit by vehicles, and at least 251 of those have been killed, with about 80% of those crashes occurring on the western side of the U.P.

The last four years have been particularly deadly, with 60 moose dying in vehicle collisions since the start of 2022. The most moose fatalities by vehicle in a single year was 20 in 2022. Six moose have died in vehicle collisions so far in 2025.

One likely reason for the increase in collisions is the core moose herd in the western U.P. has shifted south over the past 10 to 15 years as the animals seek available habitat.

A dead bull moose is shown in the grass along an Upper Peninsula highway after a moose-vehicle crash. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

Most of the moose-vehicle crashes have occurred on a handful of relatively short stretches of state or federal highways in an area bordered by southern Baraga County, eastern Iron County and southwest Marquette County.

Here are the moose-vehicle collision hotspots:

— U.S. 41 between Nestoria and the M-28 intersection in eastern Baraga County. This 10-mile stretch of highway, with a 55 mph speed limit, has seen 45 moose-vehicle collisions since 1984.

— U.S. 141 between Amasa and Covington in northern Iron County and southern Baraga County. This 23-mile stretch of highway, speed limit 55/65 mph, has seen 37 collisions.

— M-95 between Republic and the U.S. 41 intersection in southwest Marquette County. This 7-mile stretch of highway, 55 mph, has seen 24 collisions.

A graph shows months and the percentage of occurrence of moose-vehicle crashes in the Upper Peninsula. (Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

— U.S. 41 between Greenwood and the M-95 intersection in Marquette County. This 8-mile stretch of highway, 55 mph, has seen 17 collisions.

‘Unique crash hazard’

The DNR has worked closely with MDOT over the years to get moose-crossing signs installed or replaced on U.P. highways. The signs previously had an image of a moose, but those were frequently stolen, so the current signs simply state, “Moose Crossing.” There are currently half a dozen moose-crossing signs in place along U.S. 41, M-95 and U.S. 141.

But research has shown that such warning signs can lose their effectiveness over time as drivers become accustomed to seeing them on a regular basis.

The Michigan Office of Highway Safety Planning advises motorists to stay alert, heed animal-crossing signs, slow down in those stretches of roadway and use high-beam headlights and additional driving lights to see the road better.

“Moose pose a unique crash hazard in the Upper Peninsula that isn’t seen in lower Michigan,” said Alicia Sledge, OHSP director. “Residents and tourists driving in the Upper Peninsula should exercise caution when traveling in moose country.”

September is the most active month for moose deaths by vehicle, accounting for 21% of all collisions since 1984, followed by June (19%) and October (12%).

Petroelje noted that the moose rut, or mating season, occurs in September and October, when male moose (bulls), are highly active in pursuing female moose (cows).

Moose-vehicle crashes drop off drastically from November through March as the animals retreat to their winter ranges and become less active to conserve energy.

Moose-vehicle collisions pick back up in April as the animals move to their summer ranges, with a significant spike in June. That may be because the moose are trying to get away from bugs by seeking out open spaces along highways.

Not surprisingly, most moose-vehicle collisions have occurred at night, particularly between 9 p.m. and midnight. The fewest moose-vehicle collisions occur between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Stagnant moose population

Moose were reintroduced to Michigan in the mid-1980s, with a goal of reaching 1,000 moose by the year 2000. But the population has been relatively stagnant over the past decade, and the DNR and its partners are studying potential factors, including predation, disease, habitat, vehicle collisions and moose accidents or trauma suffered beyond vehicle collisions.

“We could have as many as 5% of our moose population hit and killed by vehicles in a given year,” Petroelje said. “In that sense, it’s fairly significant when we’re thinking about factors that could limit moose population growth.”

The cow killed on June 17 was wearing a GPS collar as part of the DNR’s moose research project. The collision was not reported to authorities. The calves were not collared.

The DNR collects moose-vehicle collision data from official crash reports, calls from citizens and law enforcement officers, and GPS collar mortality signals. DNR biologists confirm all reports of moose fatalities and, when possible, collect internal organs, a femur and the head for disease testing and health monitoring as part of moose mortality research.

Other states with populations of moose, such as Alaska and Maine, have hundreds of moose-vehicle collisions every year, with some resulting in human fatalities. But those states also have much larger moose populations. Alaska has about 175,000 moose, while Maine has about 60,000.

In Michigan, experts from MDOT and the DNR are analyzing moose crossings as part of another study looking at wildlife crossing hotspots around the state. The study, funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation and state matching funds, aims to identify the most problematic wildlife crossings posing a risk for motorist safety on state trunklines.

Michigan typically ranks fourth-highest in the nation for deer-vehicle crashes, with an average of 55,000 deer-vehicle crashes per year, resulting in $130 million in damages.

While the number of vehicle crashes with other large species, including moose, is not as high, the risk and damage are detrimental and increase the risk for these species.

In response to the high number of moose-vehicle collisions, DNR and MDOT officials have discussed the possibilities of installing fencing along U.P. highways or even wildlife overpasses. But these types of projects can be cost-prohibitive and complicated due to legal issues, including rights-of-way and land ownership.

What to do after crash

If you hit a moose (or any large animal), turn on your emergency flashers, stay buckled and move your vehicle to the shoulder of the road. If the vehicle is inoperable and still in the line of traffic, carefully exit and stand well off the road. Call the police to report the crash.

In addition, call the DNR’s 24/7 Report All Poaching hotline at 800-292-7800 as soon as possible so conservation officers can attempt to salvage hundreds of pounds of meat, said Sgt. Calvin Smith.

Smith, a veteran conservation officer based in Newberry, said the DNR works with area meat processors to grind the moose meat into burger, and donates it to help feed the hungry.

But conservation officers must move quickly after a moose-vehicle collision, usually within a few hours.

“When it’s warm, you’re fighting against the clock to salvage that meat,” Smith said. “Plus, they’re a big animal and take longer to field dress. They’re not something you can just pick up by yourself and throw in the back of the truck.”

Moose are one of Michigan’s most iconic wildlife species that many people would love to see. Slowing down to help prevent moose crashes, especially in the hotspot areas, also improves chances of motorists spotting a moose along highways in the Upper Peninsula.

It’s a win for researchers, conservationists, the motoring public and our Michigan moose.

To learn more about moose, go to the DNR’s moose page at https://www.michigan.gov/dnr/education/michigan-species/mammals/moose.