The Okefenokee Swamp is often associated with cypress trees and Spanish moss, but the ecosystem also includes vast prairies.

To David Walter Banks, there’s something special about the Okefenokee Swamp, the largest blackwater swamp in North America.

There’s a mystical quality, the photographer says, that’s hard to explain to someone who’s never been there before.

“It’s this spiritual, metaphysical presence,” he said. “Time and time again, people that go there explain that’s it’s just magical. It touches people’s lives when they enter the space and spend time there.”

Over the past three years, Banks has spent nearly 70 nights alone in the swamp, which stretches more than 400,000 acres from southern Georgia to northern Florida. He would stay there a few days at a time, camping on the islands or just elevated wooden platforms.

His days would consist of paddling on a boat and “doing the best I could to be completely present in the moment,” he said. “What I would photograph was whatever I saw, whatever I was drawn to.”

But there was something missing at first. His photos, by themselves, weren’t fully capturing the way it felt out there to him.

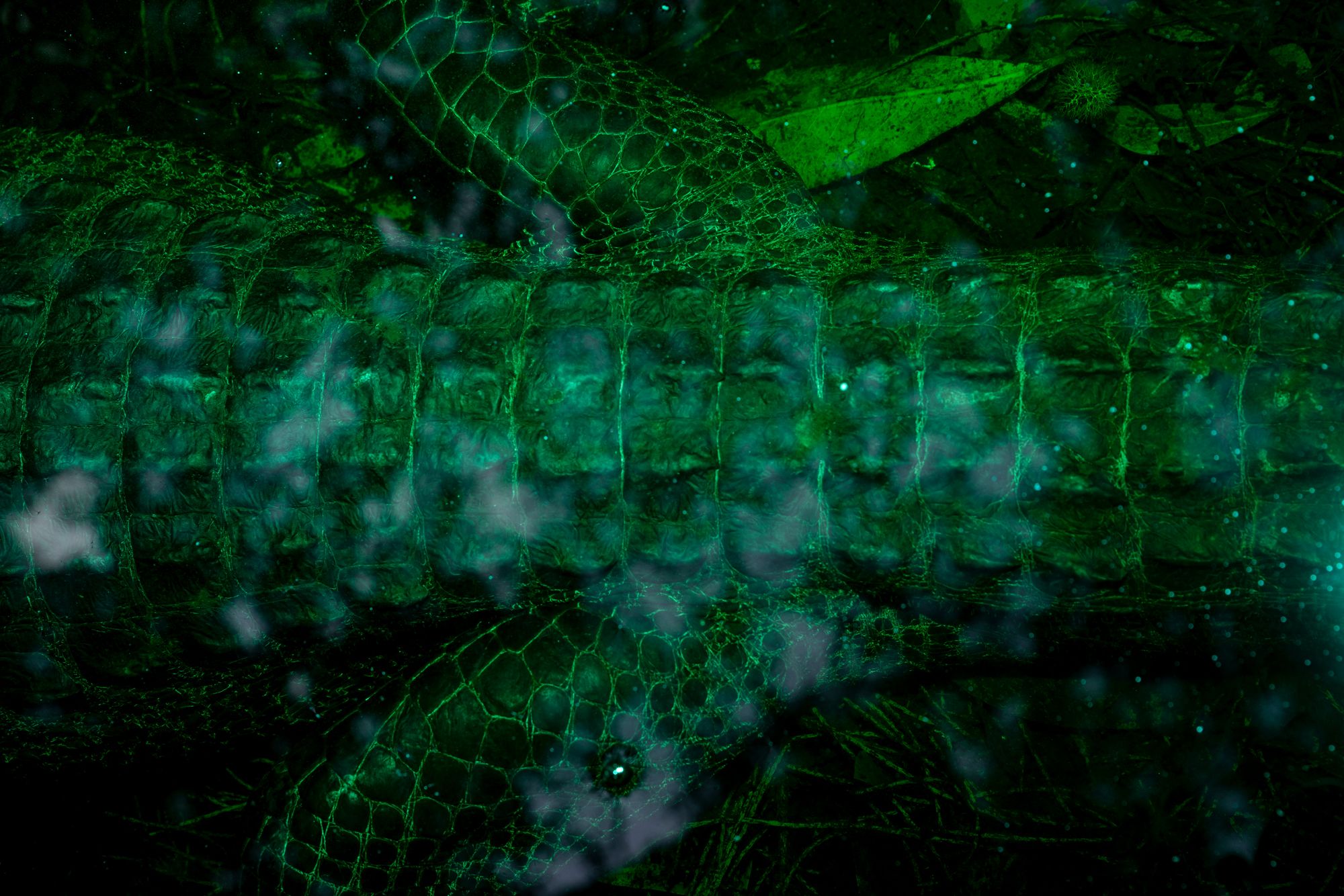

So he got creative, experimenting with different in-camera techniques to inject more color and fantastical elements to all the wildlife he’d encounter on his trips.

“I always had a love and a fascination for the way that photography can capture a moment that is more or different than what our eyes see, especially when that picture sort of hints at the surreal or magical realism,” Banks said. “It’s something that I nurtured personally, even if it wasn’t for my professional work.”

Spiders are aplenty and have ample dining options during the warm months, Banks said, when bug shirts and head covers are needed after dark.

Carnivorous pitcher plants are a staple in the Okefenokee prairies and are bunched in bouquets.

Banks’ gorgeous, almost psychedelic images make up his new book “Trembling Earth: A Transcendental Trip Through the Okefenokee.” Okefenokee has been translated as “land of trembling earth” in the the Muskogee language.

“I wanted to hint at this more spiritual, mystical feeling that people have talked about this place since (naturalist and writer) William Bartram’s travels in the 18th century,” Banks said. “It was like suddenly, all these little tricks that I had come up with, for creating an image that feels a little more surreal, I had an outlet for them.”

The effects are mainly the result of strobe lights and colored gels or filters, Banks explained.

“When I go out on these trips, I have normally two lights: one goes on my camera, or can also be used off camera, and the other is a little bit of a stronger battery-powered strobe light like you would use in a studio,” he said. “I’m often using one, if not both of those. Sometimes they’ll have different colors, like a tinted piece of plastic more or less that goes in front of the light, and then the light shoots through that and casts that color.”

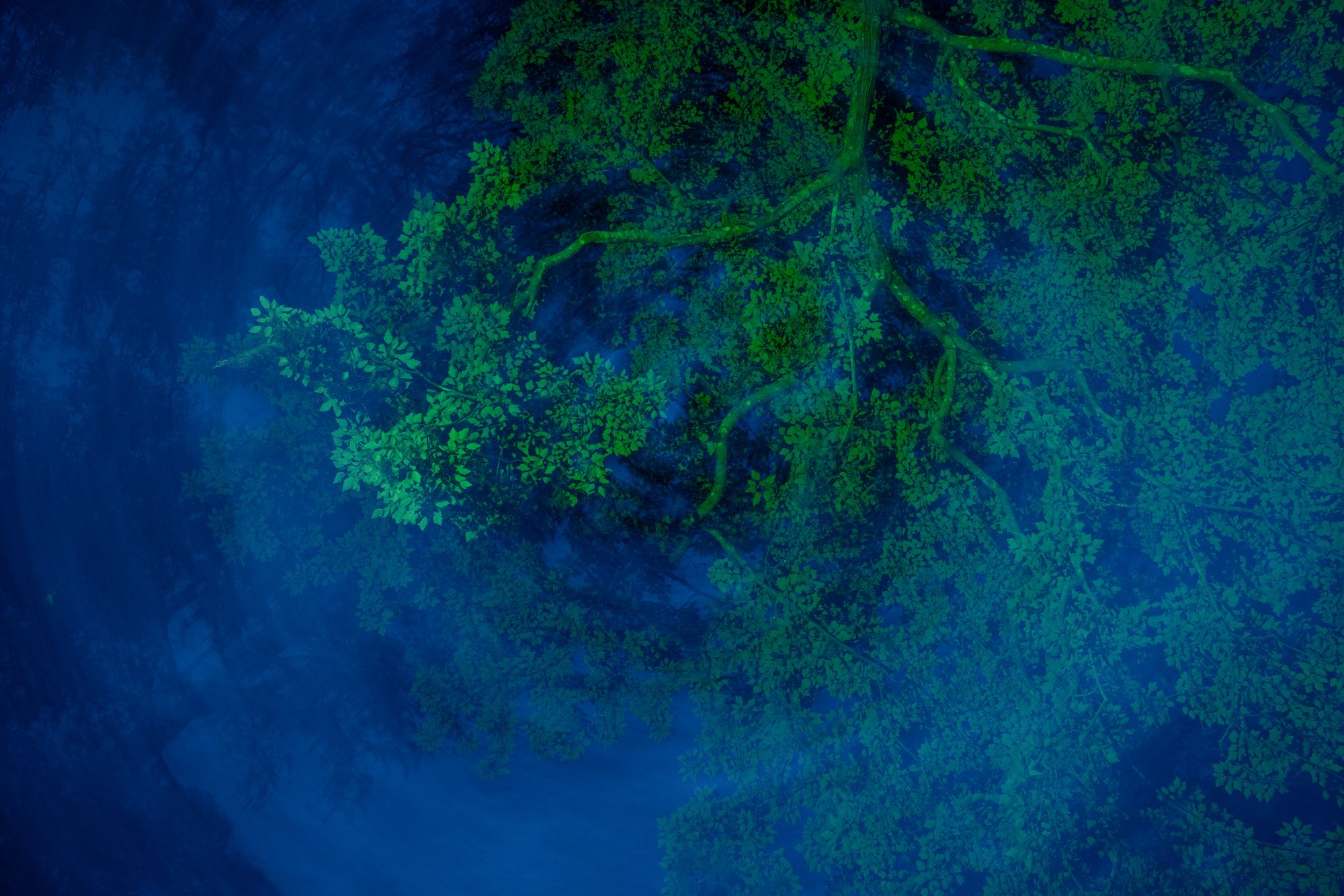

“My favorite time in the swamp is predawn, when the fog cloaks the landscape bestowing an eerie glow,” Banks said.

In this long-exposure photo, Banks shined light on the prairie grasses and then allowed the gradient of the sky to burn into the shadows.

A marsh fern is lit with color-gelled flash and layered upon itself in this triple-exposure photo taken along the Suwannee Canal.

Storm clouds fill the sky over a winding canoe trail near Monkey Lake.

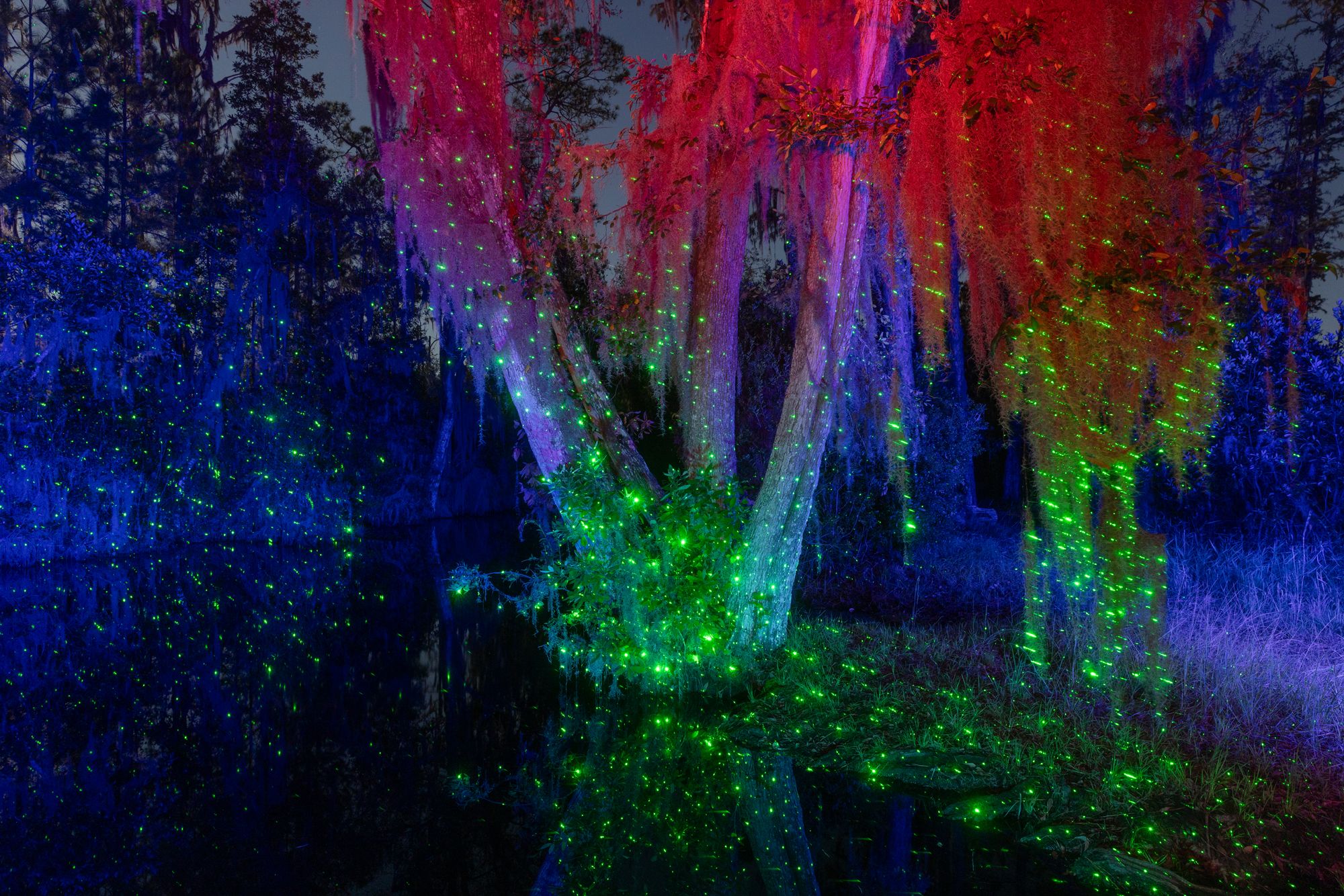

Some of the more complicated-looking images are created with a long exposure, where the camera shutter is open for multiple minutes at a time. This is especially used before sunrise and after sunset, when light is limited.

“Say I have a landscape that I like, I like how it looks. I’ll set up the camera, I’ll have it on a tripod, and I’ll have a long exposure,” Banks said. “Now, during that long exposure, I’ll be taking these two strobes, and I’ll be running around and just popping them off, just lighting different things, sometimes with different colors.

“My strobes can only reach so far, so I’ll also bring these high-powered, tiny flashlights. I’ll take those same gels that I put over my strobes, and I’ll use my hand and cover these flashlights. I’ll use those to sort of paint in things are that are off in the distance.”

These techniques help the images feel more emotive to Banks. But there’s also another benefit: They grab your attention.

“I think people are just bombarded with visual stimuli these days. … Part of this is also kind of jerking people out of that scroll malaise and making them stop and look at the photo and question it,” he said.

Banks wants to use his book to raise awareness about the swamp and some of the threats it has faced in the past and possibly in the future. Environmental advocates recently helped put a stop to a proposed titanium dioxide mine at the Trail Ridge, which borders the swamp on its eastern boundary. There were concerns that the mining could have lowered the water levels of the swamp and made it more susceptible to wildfire.

The Conservation Fund stepped in to purchase an 8,000-acre tract of land from the mining company that was applying for permits, but Banks says the swamp won’t be fully protected until safeguards are put on all the waterways and land that surround it.

Big Water Lake before dawn, surrounded by fog. “The area was so shrouded I ended up paddling a mile in the wrong direction, adding two miles to my day’s journey,” Banks remembered.

A double exposure of flowers blooming on the prairie.

“This place is a National Wildlife Refuge, so the actual space is protected — but the boundaries are not,” Banks pointed out.

He is passionate about protecting the swamp, which has been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, so that future generations can enjoy it. It’s one of the largest intact freshwater ecosystems in the world, he said, with incredible biodiversity that includes rare and endangered species such as the gopher tortoise.

“Wetlands, they’re like our redwood forests of the South,” he said. “These are where our gigantic trees are. These are where our prehistoric trees are. And more than half of the wetlands in the lower 48 states are already gone, according to the US Fish and Wildlife Service.”

Since his first night in the swamp, when he was serenaded by a symphony of frog songs, owl calls and alligator bellows, Banks has fallen in love with the Okefenokee and the way it makes him feel.

Sometimes there’s a great quiet, an emptiness where he can center himself and find refuge from the hustle and bustle of daily life. At other times, it can be chaotic and challenging, with intense storms that remind him of nature’s unrelenting force.

All of it gives him a greater appreciation for life, which he explains more in his book.

“This is no comprehensive record of facts between these covers, but it is one of truth — the truth of my experience,” he writes. “One of newfound awareness and revelation, and interconnectedness. I hope ‘Trembling Earth’ captures not only what can be seen, but what can be felt — the unmistakable yet ineffably mystical quality of this primordial space.”

David Walter Banks’ book “Trembling Earth” was published by The Bitter Southerner and is now available.