India’s metals trade pattern demonstrates a structural asymmetry; exporting low-value bulk while importing high-value niche inputs, exposing vulnerabilities that constrain downstream industrialisation and compromise resilience.

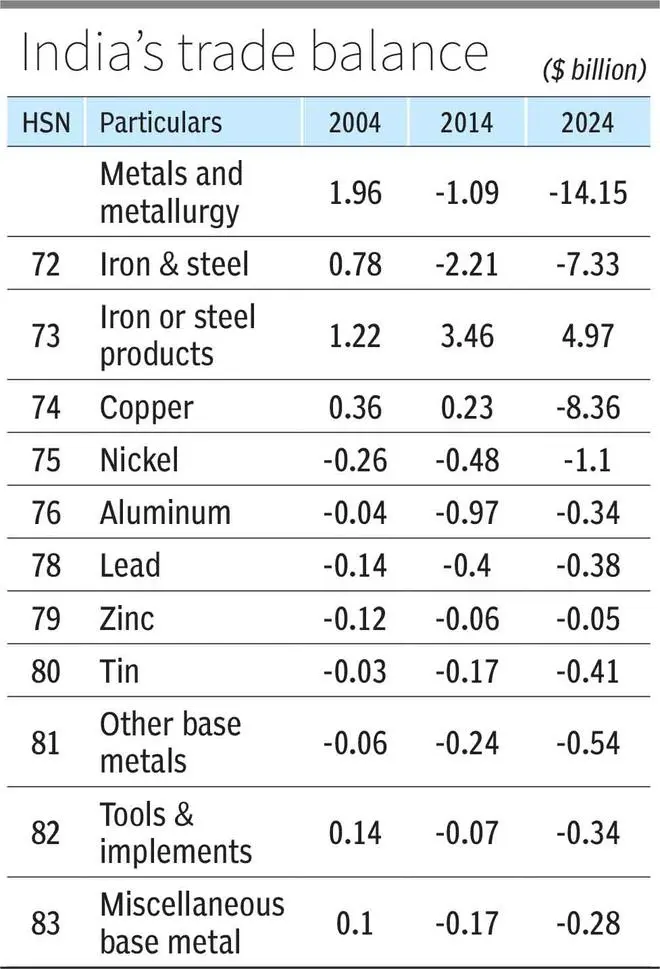

The country today stands at an inflection point in the Metals & Metallurgy Industry (MMI) constituting HSN:72-83, where trade imbalances have grown from episodic fluctuations into a structural liability. Illustratively, India’s metals deficit reached $14.15 billion in 2024, making up (-)5.4 per cent of the overall trade deficit of $261 billion. In last two decades, India has become a net importer, from being an exporter in 2004 with $1.96 billion surplus.

India possesses abundant ores but has failed to convert this advantage into durable industrial strength, with persistent deficits in copper, nickel, tin, and lead offsetting only modest surpluses in iron and steel articles and occasional gains in aluminum.

Structural crossroads

The country’s MMI trade trajectory underscores widening product-level vulnerabilities. Copper (HS:74) exemplifies the sharpest decline, shifting from a modest surplus of $0.36 billion in 2004 to a deep deficit of $8.36 billion in 2024, aggravated by the closure of Sterlite Copper and import dependence on Chile and Africa. The FTAs India has entered into have also contributed as a conduit of re-routing and rampant dumping of metals, undermining domestic industry potential.

Likewise, Nickel (HS:75) has remained structurally negative, deteriorating from $(-)0.26 billion in 2004 to $(-)1.10 billion in 2024, with no overseas acquisitions to offset domestic scarcity. Iron and steel (HS:72), once India’s flagship export, fluctuated dramatically, recording a $9.52 billion surplus in 2021 before collapsing into a $(-)7.33 billion deficits by 2024. Aluminum (HS:76) briefly moved into surpluses in 2021 but returned to deficit by 2024.

The structural crossroads reflect multiple vulnerabilities cutting across resources, technology, and policy. Smaller categories such as tin, zinc, and lead persistently show deficits, reflecting limited refining, weak recycling, and shallow value-addition, compounded by resource scarcity, high energy costs, outdated smelting technology, fragmented recycling systems, poor R&D intensity, policy volatility, infrastructure bottlenecks, compliance pressures, and sub-scale production.

Despite abundant iron ore and bauxite, India exports significant volumes in raw or semi-finished form, while higher-value steels and alloys are imported. This shallow value addition highlights fragility in industrial depth. The market is fragmented, with many small-scale players, some medium firms, and only a few large enterprises, producing oligopolistic behaviour where scale, productivity, supply-chain control, energy efficiency, and market access determine competitiveness.

Recycling remains embryonic. Aluminum scrap, lead-acid batteries, and e-waste are handled mainly by informal operators lacking scale, technology, and safeguards, with poor collection systems, low material recovery rates, absence of standardised protocols, weak regulatory enforcement, and minimal investment in modern recycling infrastructure, resulting in environmental hazards, resource leakages, and missed opportunities to build a robust secondary supply base.

As a result, India misses a reliable secondary supply-base that could buffer against global volatility and reduce dependence on imports.

Innovation in metallurgy is sparse, underpinned by weak institutional capacity. Alloy research, lightweight composites, and green metallurgy remain underfunded, while unpredictable policies on tariffs, royalties, and mining approvals deter long-term investment. This leaves India reliant on external supply chains dominated by China, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, embedding risks of volatility and geopolitical leverage.

Meanwhile, India’s appetite for metals is rising rapidly, driven by infrastructure, renewable energy, electric mobility, and aerospace. While iron ore and bauxite reserves offer a natural anchor, integration into higher-value chains is essential. Green steel, low-carbon aluminum, and scaled recycling could create a circular economy, while production-linked incentives and trade agreements can embed India more deeply in global value chains.

By contrast, China illustrates the power of scale, scope, sophistication and orchestration. It produces over half the world’s steel and aluminum, dominates copper smelting and nickel processing, and secures overseas mining stakes to lock supply chains. Unlike India, which exports ores and imports alloys, China has built a fully integrated value chain from extraction to engineered exports, supported by R&D and green metallurgy pilots, positioning itself as architect and price-setter of the global metal’s economy.

Way forward

Reducing India’s trade deficit in metals and metallurgy requires a strategy that fuses resource security with industrial depth and sustainability. The recent Carlsberg Ridge acquisition, granting India a 15-year exploration contract for polymetallic sulphides, exemplifies how seabed initiatives can address shortages of copper, nickel, cobalt, and other critical minerals. Alongside earlier allocations for polymetallic nodules and cobalt-rich crusts, such initiatives diversify supply sources, reduce import dependence, and create strategic autonomy in the mineral space.

Moreover, India should expand domestic smelting and refining capacity in copper, aluminum, and nickel, supported by PLI-style incentives for speciality steels, lightweight alloys, and advanced materials. Building industrial clusters in port-based corridors that co-locate smelters, alloy plants, and recycling hubs can replicate integrated ecosystems seen in China. Simultaneously, organised recycling of copper, aluminum, and e-waste, underpinned by recovery targets and extended producer responsibility, can integrate circularity and ease pressure on imports.

Lastly, innovation and green transition must complement these efforts. Hydrogen-based steelmaking, renewable-powered aluminum smelters, and sustainable metallurgy can open access to ESG-sensitive markets. By combining domestic reforms with strategic ISA’s approved seabed explorations in Indian Ocean, India can transform from a resource-constrained importer into a globally competitive, investment-attractive alternative to China.

The writers are with IIFT, New Delhi. Views expressed are personal

Published on October 25, 2025