Rift Valley Fever (RVF) is a viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes that mainly affects livestock. It can also infect humans. While most human cases remain mild, it can cause death. The disease causes heavy economic and health losses for livestock farmers.

As a researcher, I have contributed to several studies on this mosquito-borne virus.

So, what exactly is Rift Valley fever, how it is treated, and how it can be controlled?

What is Rift Valley fever?

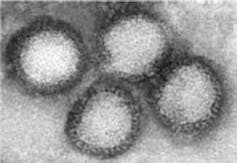

Rift Valley fever is a zoonosis (a disease affecting animals that can be transmitted to humans). It is caused by the RVF virus, a phlebovirus from the Phenuiviridae family (order Bunyavirales). The disease primarily affects domestic animals, mainly cattle, sheep and goats, but also camelids and other small ruminants. It can occasionally infect humans.

In animals, the disease causes high morbidity: reduced milk production, high newborn mortality, mass abortions in pregnant females, and death in 10% to 20% of cases. This leads to serious economic losses for farmers.

Most people who get Rift Valley fever have no symptoms or just flu-like syndrome. But in a few people, it can become very serious, causing complications such as eye disorders, meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the brain), or hemorrhagic fever. The fatality rate among infected people is around 1%.

How it’s transmitted

In animals, the disease is mainly spread through bites from infected mosquitoes. At least 50 mosquito species can transmit the Rift Valley fever virus, including Aedes, Culex, Anopheles and Mansonia species. Mosquitoes become infected when they feed on animals carrying the virus in their blood, then transmit it to other animals through their bites. In Aedes mosquitoes, vertical transmission – from infected females to their eggs – is also possible, allowing the virus to survive in the environment.

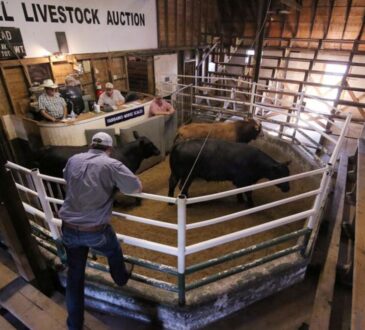

For humans, the most common way to get infected is through direct contact with the blood or organs of an infected animal. This often happens during veterinary work, slaughtering, or butchering.

While it is also possible for human to get the virus from a mosquito bite, this is not common. No human-to-human transmission has been observed to date.

The origins and spread

A serious outbreak of Rift Valley fever began to be reported in Senegal in late September 2025. The west African country has been battling to control it.

The disease was first discovered in 1931 in the Rift Valley in Kenya in east Africa, during a human epidemic of 200 cases. The virus itself was isolated and identified in 1944 in neighbouring Uganda.

Author provided (no reuse)

Since then, numerous outbreaks of the disease have been reported in Africa: in Egypt (1977), Madagascar (1990, 2021), Kenya (1997, 1998), in Somalia (1998), in Tanzania (1998), the Comoros (2007-2008) and Mayotte (2018-2019).

In west Africa, the main epidemics affected Mauritania (1987, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2010, 2012), Senegal (1987, 2013-2014) and Niger (2016).

Its spread into the Sahel and west African regions has been largely driven by the movement of livestock, and by environmental factors.

To date, around 30 countries have reported animal and/or human cases in the form of outbreaks or epidemics.

Why and how outbreaks occur

Rift Valley fever reemerges in cyclical patterns, with major outbreaks occurring in Africa every five to 15 years. The trigger for these outbreaks is closely linked to specific environmental conditions, like periods of heavy rainfall that create ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes.

In east Africa, epidemics typically follow periods of exceptionally heavy rainfall or flooding in normally dry regions. For instance, the severe outbreaks of 1998-1999 were directly linked to intense rains caused by the El Niño climate phenomenon.

Read more:

West Africa’s trade monitoring system has collapsed – why this is dangerous for food security

In the Sahel region, the relationship with rainfall is less predictable. Outbreaks can appear in unexpected, poorly monitored areas, and genetic analysis of viruses in Mauritania suggests that new strains can be introduced directly from other regions.

A key mystery is how the virus persists in the environment between these major outbreaks. It is believed to survive in the environment within a “wild reservoir” of animals – such as certain antelopes, deer, and possibly even reptiles – though this reservoir has not yet been fully identified.

Once an initial outbreak occurs, the virus can spread to new areas. This happens through the movement of infected livestock, the accidental transport of infected mosquitoes (for example, in vehicles or cargo), and when environmental conditions are conducive.

Clinical symptoms and treatments

Adult cattle and sheep may show nasal discharge, excessive salivation, loss of appetite, weakness, diarrhoea.

In humans, after an incubation period of two to six days, most infections are asymptomatic or mild, with flu-like symptoms lasting four to seven days. People who recover from the infection typically gain natural immunity.

Read more:

Preventing the next pandemic: One Health researcher calls for urgent action

However, in a small percentage of individuals, the disease can take a severe turn:

-

Eye lesions affect up to 10% of symptomatic cases. They appear one to three weeks after initial symptoms and can heal on their own or lead to permanent blindness.

-

Meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the brain and meninges) occurs in 2%-4% of symptomatic cases, one to four weeks after symptom onset. Mortality is low, but neurological after-effects are common.

-

Hemorrhagic fever (diseases that cause fever and bleeding due to damage to the blood vessels) occurs in less than 1% of symptomatic cases, usually two to four days after symptoms begin. About half of these patients die within three to six days.

There is no specific treatment for severe cases of Rift Valley fever in humans.

Surveillance, prevention and control

Veterinary surveillance with immediate reporting and monitoring of infection in animals is essential to control the disease. During outbreaks, controlled culling of infected animals and strict restrictions on the movement of livestock are the most effective ways to slow virus spread.

Read more:

How does Marburg virus spread between species? Young Ugandan scientist’s photos give important clues

As with all mosquito-borne viral diseases, controlling vector populations is an effective preventive measure, though it is challenging, especially in rural areas.

To prevent new outbreaks, animals in endemic regions can be vaccinated in advance. A modified live virus vaccine provides long-term immunity after a single dose, but it is not recommended for pregnant females because it can cause abortions. An inactivated virus vaccine is also available, it avoids these side effects, but it requires several doses to provide adequate protection.

Threat, vulnerabilities and health risks

People at highest risk of infection include livestock farmers, abattoir workers and veterinarians. An inactivated vaccine for human has been developed. But it is not licensed yet and has only been used experimentally.

Raising awareness of risk factors is the only effective way to reduce human infections during outbreaks. Key risk factors include:

-

handling sick animals or their tissues during farming and slaughter

-

consuming fresh blood, raw milk, or meat

-

mosquito bites.

It is important to follow basic health precautions when Rift Valley fever appears. Wash your hands regularly. Wear protective gear when handling animals or during slaughter. Always cook animal products such as blood, meat and milk thoroughly. Use mosquito nets or repellents consistently.