- Mongabay has begun publishing a new edition of the book, “A Perfect Storm in the Amazon,” in short installments and in three languages: Spanish, English and Portuguese.

- Author Timothy J. Killeen is an academic and expert who, since the 1980s, has studied the rainforests of Brazil and Bolivia, where he lived for more than 35 years.

- Chronicling the efforts of nine Amazonian countries to curb deforestation, this edition provides an overview of the topics most relevant to the conservation of the region’s biodiversity, ecosystem services and Indigenous cultures, as well as a description of the conventional and sustainable development models that are vying for space within the regional economy.

- Click the “A Perfect Storm in the Amazon” link atop this page to see chapters 1-13 as they are published during 2023 and 2024.

New roads open wilderness landscapes to development, and commodity markets drive the expansion of the agricultural frontier. These two causes of deforestation are at the centre of deforestation policy discussions. A third factor – land values and their tendency to appreciate over time – is a synergistic product of these two phenomena. Understanding the dynamics of rural real estate markets is essential in devising policies to halt the advance of the conventional economy into the forest wilderness.

The agricultural frontier in the Pan Amazon is the product of centuries of cultural tradition and decades of economic policy. This phenomenon, which is central to the history of the Western Hemisphere, became a major disruptive force in the Pan Amazon only in the 1960s, when governments implemented programmes to occupy and develop their Amazonian hinterlands.

Unlike previous colonisation periods, such as the rubber boom of the nineteenth century, this latter period included initiatives to promote the mass migration of families into the region, which were combined with strategies to attract investment in market-based production systems. These policies were contingent on the offer of free, or nearly free, public land.

Access to land was conditional, however, and pioneers had to install a productive enterprise, which obligated them to replace natural vegetation with cultivated plants. Official policies have changed, but this practice continues to motivate individuals on the forest frontier, where people clear forest as a strategy to project ownership of land they view, rightly or wrongly, as their own.

Most believe they are acting in the best interest of their families and their country by generating economic activity. They are aided and abetted by functionaries in agricultural ministries who implement outdated policies that facilitate the transfer of public lands to private individuals. Layered on top (or underneath) this dysfunctional regulatory framework is a culture of graft, impunity and entitlement.

Rural real estate markets regard land as part commodity and part capital asset. As a commodity, its price is mediated by supply and demand: Parcels near to the forest frontier are less expensive because there is an available supply that can be acquired at low cost. As the forest frontier recedes, land appreciates in value as it becomes a more limited commodity. As a capital asset, properties increase in value with investment in on-farm infrastructure and perennial crops that generate cashflow over the short-term, such as coffee, cacao and oil palm, as well as timber species that pay a substantial dividend over the medium term.

Other considerations influence the price of land. If the soil is arable, land has additional value because farming is more lucrative than ranching. Forest remnants may or may not have commercial value, depending on whether they retain stands of hardwood timber. Despite their intrinsic value, degraded forests are viewed as ‘unproductive’ – unless they have been converted into ‘productive land’ dedicated to conventional agriculture. All too frequently, landholders will first monetize the value of their timber and then use that capital to finance the conversion of the degraded forest into pasture or farmland.

The economics are straightforward: a pasture can support cattle and generate cash flow of ~ $200 per hectare annually, or $2,000 over ten years. This is a reasonable return on an investment that require a rancher to clear the forest, build fencing and construct a water impoundment at a cost of about $500 per hectare. More importantly, the value of land itself will appreciate over time, reflecting both the improvement of on-farm infrastructure and the generally upward direction of real estate markets (see below). Similar economic calculations drive investment decisions on smallholder landscapes, where properties can experience a step-change in value with the establishment of a perennial crop like coffee, cacao or oil palm.

Pioneer families are active participants in rural real estate markets. They use their knowledge of soil, water and natural vegetation to develop additional landholdings that they sell to investors and newly arrived migrants. Some become frontier entrepreneurs who specialize in the acquisition and development of properties. Many are businesspeople who are ‘improving’ properties deforested during previous cycles of settlement. One of their main marketing tools – and a core service – is to complete the titling process. A certified legal title significantly enhances the market price of a property.

Unfortunately, legitimate real estate investors share the marketplace with unscrupulous individuals who invade public lands or displace families who have informally occupied them. Referred to as ‘land grabbers’ in the English-language media, in Brazil they are known as grileiros and in Spanish speaking countries as traficantes de tierra.

The Distribution of Public Lands

Public lands have been, and continue to be, distributed via a variety of legal, quasi-legal and blatantly illegal mechanisms. These mechanisms have evolved over time, but they can be broadly organized into four main categories:

1. State-sponsored colonization schemes

This policy was predominant during the 1970s and 1980s and was managed by agencies with various names and acronyms (Table 4.1). Approaches varied among countries, but all targeted the rural poor and distributed landholdings between forty and 100 hectares. Some were organized via a communal tenancy regime while others ceded plots to individual families. Only Brazil continues to distribute land among its citizens via projects organized by a national agency, or it did until 2017 when an audit led to a temporary suspension of its activities (see Chapter 6).

2. Direct land grants or sales by the state

This mechanism was widely used in Brazil over several decades but was most prominent in the 1970s when Amazonian development was a core policy of the military government. The distribution of large landholdings led to the development of the agro-industrial model that dominates the economy of Mato Grosso, Eastern Pará and Tocantins. A similar phenomenon occurred in Bolivia, where military governments distributed land to influential families using the agrarian reform institution originally created to address land tenure inequality. Large land grants in Ecuador led to the establishment of two large-scale oil palm plantations in the early 1980s. The most recent example comes from Peru, where an influential corporation obtained large tracts of natural forest in 2005 to establish that country’s largest oil palm plantation.

3. Privately sponsored colonization schemes

This type of land distribution is a variant of the previous mechanism in which the state would grant a concession to a private company or cooperative that would subdivide and resell plots to settlers (see Chapter 6). This method promoted a middle-class farm model based on properties that range from a few hundred to several thousand hectares. It was a common business model in central Mato Grosso between the late 1950s and the early 1980s. Mennonite immigrants have employed a variant of this scheme in Bolivia, where a group of families collectively purchase a large private property, which they subdivide among themselves to create a ‘colony’ of 100-hectare family farms. This system is being replicated in Peru and Colombia, where Mennonite immigrants have been accused of clearing forest on landscapes zoned for forest management. Mennonites are not known to invade public lands, choosing instead to purchase land from intermediaries, a tactic that improves the probability they will obtain legal title.

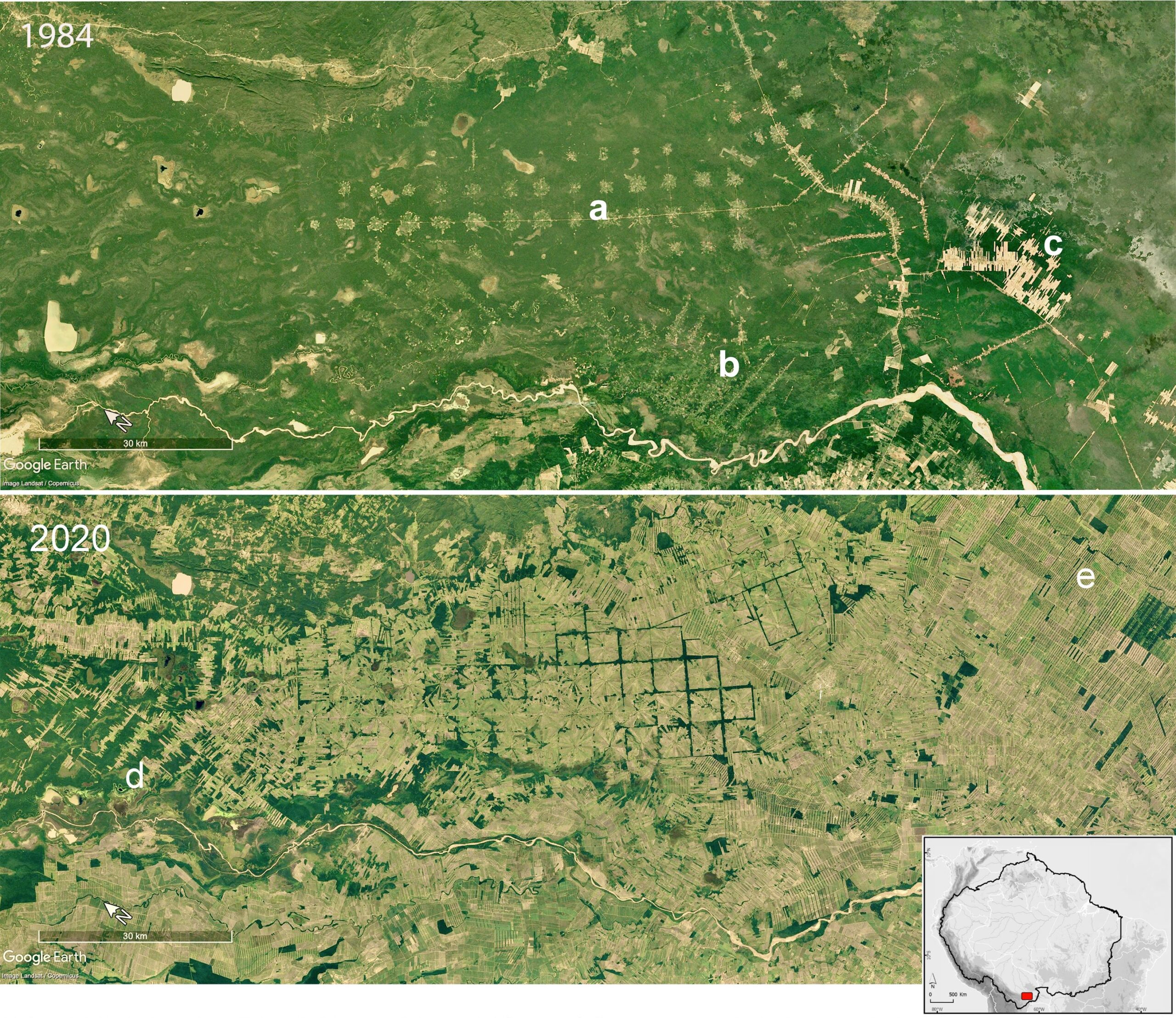

4. Spontaneous settlement and land grabbing

The appropriation of public lands via informal and blatantly illegal processes is common on all the forest frontiers in both the Andean republics and Brazil. It can occur as a land rush when a new trunk highway is created through a pristine forest landscape, but more often it occurs over decades as secondary road networks expand outward from a trunk highway. In the 1980s, governments facilitated this process via special initiatives created to respond to petitions from interest groups and regional governments. Depending upon the social and political environment, it can lead to the proliferation of large properties or small landholdings or a mixture of both.

“A Perfect Storm in the Amazon” is a book by Timothy Killeen and contains the author’s viewpoints and analysis. The second edition was published by The White Horse in 2021, under the terms of a Creative Commons license (CC BY 4.0 license).

Read the other excerpted portions of chapter 4 here:

Chapter 4. Land: The ultimate commodity